I’m not Arthur Marshall – I’m not Philip Larkin, even – but I like old girls’ stories. That’s not an easy confession to make in public, so let it be rendered clear and absolute that there are no dubious sexual connotations involved, just the arcing/arching eye of the amateur historian, prevented by his own mental condition and social limitations from ever formalising his study, and in any case taking – as previous generations generally didn’t, or at least found harder – from anywhere, however obscure or ostensibly insignificant or arcane.

And yet in the end I always walk away rather exhausted and melancholy from charity shops, the places where you can most easily chance upon these things; there are just too many memories which for me aren’t even that, too many ghosts that even I don’t really want to awaken, too many echoes of Ray Davies singing, as he suddenly realises that his vision of a world he never knew is not only doomed but might even destroy him in the end, “don’t show me no more please”, too strong a resonance of Morrissey admitting he will never go back to the old house, because in the long run that is no way of fighting the battles on whose frontline the late Tony Benn stood, the one thing less satisfactory than the capitalism of Miami Vice and Five Star (which is why it is so apt that the Would-Be-Goods – who, at a few isolated and sporadic moments these last thirty years, have made the records Florence Welch and Laura Marling should have made – ended up covering the song; their world, the utter opponent of Morrissey’s world in the decades of class war, was doomed by the same forces long term, and they knew it).

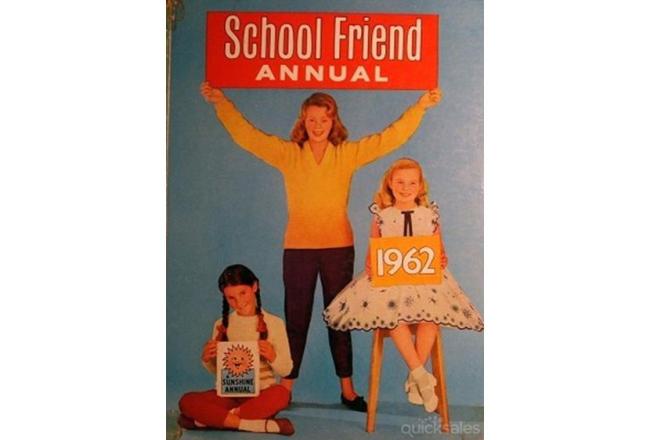

So it’s not often now that I walk into one of these places to dredge up what is rotting wood (to quote from another of the definitive texts of 1988) and whenever I do, it usually tells me something depressing about the things I find depressing, without having remotely intended to do such a thing. Sometimes there’s a surprise: just this week, amid all the usual suspects (the biggest sellers of the recent past, when the CD format was still a cash cow, who nobody had any real feeling for even at the time: Boyzone, Dido, Stereophonics, all the long-term Then Play Long problems) I came across Skinnyman’s Council Estate of Mind. But then there was the book which appears at the top of this post, and suddenly I had a new insight into how and why we are what we are today, without – in pop terms – even the radical capitalism of an early Now or Hits album.

In 1961 (almost all British annuals were produced in the year before the one that appears on the cover) School Friend found itself half in existential crisis, half calm and collected: it knew that the world it had represented was dying, but it still had a reasonable confidence for the future because the world that now presented itself – the world of the Bobbys and Gidget – required a relatively seamless adaptation. The one time – until our time – when we had a technological, pop-culture-driven future which was wholly compatible with unrepresentative elite rule. So it now advised its readers on how to barbecue hamburgers (authentically socially avant-garde at the time, especially if we use this term – relating to the 1960s – as Ian MacDonald used it), gave many more tips on the embryonic manifestation of what would now be called style culture, and compared to their earlier annuals, the stories are set much more elsewhere in the Anglosphere (Australia or Canada as classless idylls where you wouldn’t even have to leave the reassurance of home comforts behind) and much less in English girls’ boarding schools.

When this period first fascinated me, it did so because it represented an alternative, parallel model for modernity and the present which had happily been left on the fire, but which intrigued as a means through which we could have escaped Edward German and The Arcadians without anything else much changing at all. Imagine, I used to say around 1997, if the models for mass culture weren’t “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” but “War Paint” and “Ain’t Gonna Wash for a Week” by the Brook Brothers! But I didn’t know at that point that history would bite back, and that such an alternative vision would actually come to be, with disastrous consequences for the whole of British public and political culture, or what is left of either.

Some time around 2002 or 2003, British mass culture and consumerism slipped into a sort of ersatz 1961, where the social advances of a third of a century – a period topped and tailed by otherwise very different utopian-modernist Labour moments – were quietly and subtly thrown on the fire. Because this was done in a quiet and unobtrusive manner, and because technological advances obviously weren’t reversed, most people didn’t realise that this was what was happening. Most people, no doubt, couldn’t really believe it. Most people still haven’t, and this is why they get the Cameron government so wrong. But this is, indisputably, what happened at that point: Coldplay as a new model of paternalistic, caring capitalist (a sort of in-place-of-strife One Nation Toryism, as if what would follow would even be that good, or that equal), Simon Cowell as Carroll Levis, his proteges (all classes now seamlessly together) as Adam Faith.

All the good stuff in British pop comes from the twin moments of Tory crisis of confidence: Suez / Donegan and Profumo / Beatles. All the stuff worth fighting for – all the stuff that, perhaps, Tony Benn’s failure to understand was his greatest fault, all the stuff that the late Stuart Hall did understand in the face of mass resistance from his comrades – comes from those twin moments of ruling-class retreat and working-class assertion of unity with other oppressed peoples. All the bad stuff comes from the moment in between, the consumer boom of which that School Friend annual is a perfect artefact (the Girls’ Crystal annual published at the same time even had white picket fences on the cover!) – the moment of one-way, passive absorption of the overclass. And, as if in revenge for UK Garage’s great moment of crossover, and the genuine insurrection that followed (the last time I ever paid attention to Top of the Pops was when I saw Oxide & Neutrino doing “Rap Dis” and thought to myself that this could be as great a culture-war moment as ever seen on British television, if only the mass audience had still been paying attention, or seen it as part of their vague responsibility, or been doing anything other than watching Coronation Street), the legacy of the consumer boom bit back and swept all before it (there’s a whole other article to be written about how the initial launch of 1Xtra, which wouldn’t have happened without the UKG moment, actually helped to push it back underground until non-FM radio became easier for most people to hear most of the time, and the ruling class had bigger fish to fry).

Suddenly – the Golden Jubilee was also a huge factor, showing that pop and aristocracy could co-exist seamlessly and without any sense of crackling tensions and divisions – it really was like the Beatles had never happened (this is why Alex Niven’s sense of Definitely Maybe as an “end of history” album is so apt). We’d restarted as if the British future of 1961 (I have to specify British because this was, very definitely, not JFK’s future) had been the model and blueprint – in other words we were now in a situation which had only applied for a very few short years before it appeared to be yeah-yeah-yeahed into oblivion in the last quarter of 1963: where technology and pop-culture-driven modernity were compatible with unaccountable quasi-aristocratic rule, and everyone else frozen out of the mechanisms of power. The Brook Brothers really had been more influential than the Beatles! The relevance of this to how and why the present British political situation could happen should be too obvious to need further hammering home.

In pop terms, happily, such a situation didn’t entirely last. From the very late 2000s onwards there has, in terms of the singles chart, been some kind of resurgence of the Beatles lineage, the lineage of hybridisation and cross-fertilisation. But the people who set the tone for the current political state of affairs – Lily Allen as the ultimate useful idiot, the ultimate Tory sticking plaster – cannot leave us alone, cannot break apart from us. And they are hardly likely to when they know that, without them, it would have been that much harder for most members of the current government, the Mayor of London and even the Archbishop of Canterbury (there’s a whole other Christian-socialism-as-establishment-culture parallel history of the immediate post-1945 years if William Temple had lived, with potentially serious aftereffects for the British Left and British pop) to get where they are. And if seeing a schoolgirl annual brings on such thoughts and such desperations, it should be obvious why I don’t usually choose to enter those ghost ships that don’t know they are anything of the kind, why – more than ever – I prefer not to fan the embers long enough to sometimes catch their flames.

Recent Comments